This Annual Bike Ride Connects Cherokee Youth to Their History

By: Kiran Herbert

Every June, a cohort of bicyclists “Remember the Removal” by traveling nearly 1,000 miles from Georgia to Oklahoma, honoring their ancestors along the way.

In 1984, when Will Chavez was 17, he signed on to participate in a month-long, multi-state, 950-mile bike ride. A member of the Cherokee Nation, Chavez grew up in Eastern Oklahoma where he’d spend summer days riding a one-speed motocross bike with his cousins, exploring nearby Marble City and the local creek, where they’d go swimming. By the time he was finishing high school, Chavez was invited to participate in the inaugural Remember the Removal Bike Ride.

Founded by Mike Morris and Mose Killer, the Remember the Removal ride was envisioned as a way to better involve youth in their Cherokee culture. The school in Marble City only goes through eighth grade and about a third of kids often drop out when it comes time to transition to high school. Morris and Killer saw a need to cultivate leadership qualities in Cherokee youth, as well as help them build self-esteem and confidence to face life’s challenges. The pair settled on a bike ride that would not only test the youth mentally and physically but also allow them to honor their shared history.

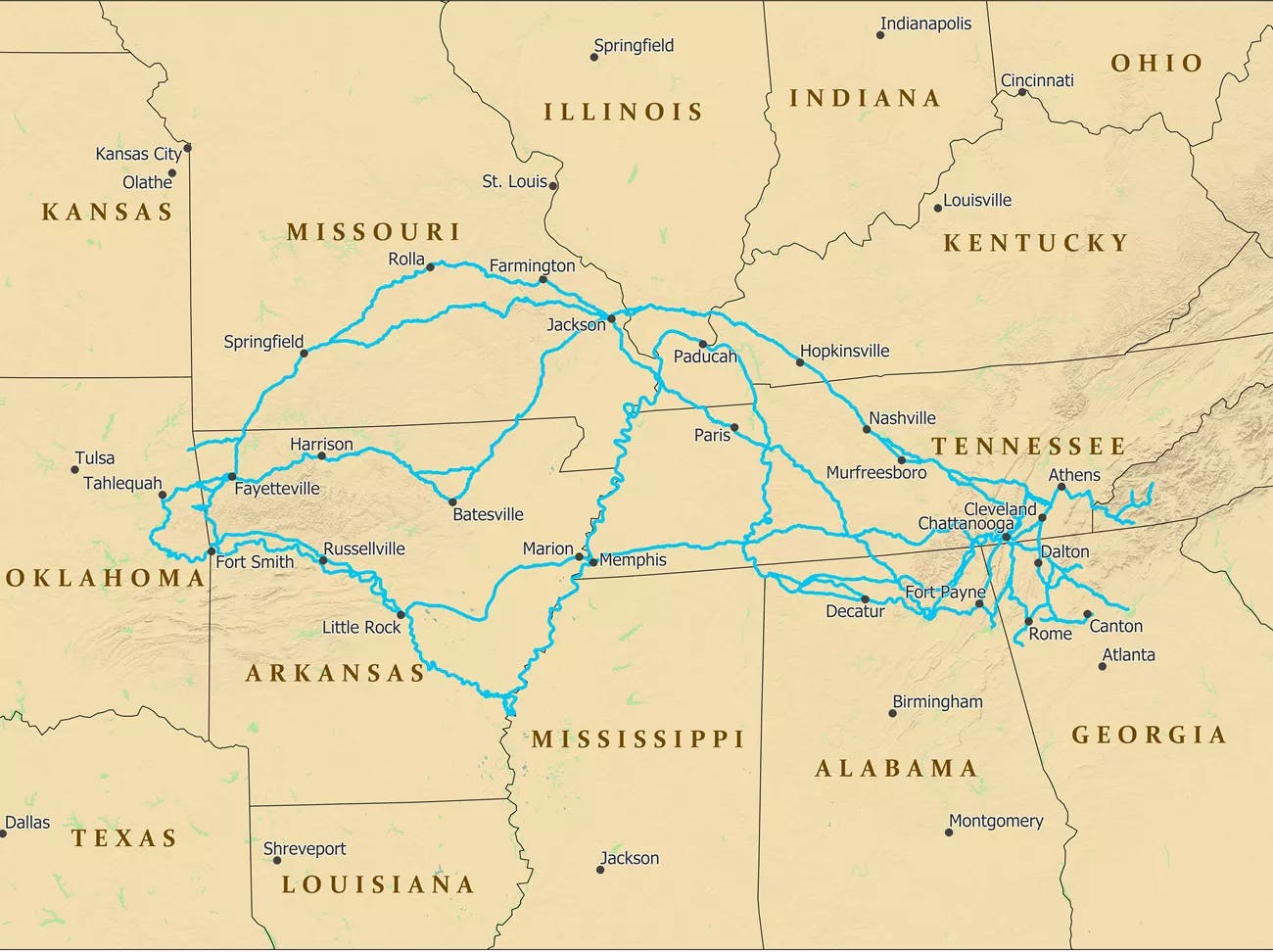

The Remember the Removal Bike Ride retraces the Trail of Tears, a forced displacement campaign from the U.S. government that doubled as a form of ethnic cleansing. Between 1830 and 1850, some 60,000 people from the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their homes in the southeastern United States and relocated west of the Mississippi River. The relocation to less fertile land took months, and more than 4,000 people died from exposure, disease, and starvation.

The Trail of Tears is actually a network of different routes — Remember the Removal riders stick to the northern route.

By recreating the original route as a bike ride, Cherokee leadership hoped to expose youth to the hardships their ancestors faced when they made the same trek on foot decades before. That first year, Chavez joined 19 other students and ride coordinators on bikes, while support vans and a school bus followed with tents, food, and other necessary supplies. The group visited historical sites as they followed in their ancestor’s footsteps, averaging 60 miles a day. For Chaves, the trip was life-changing.

“Before the ride, my self-esteem was not good and I didn’t have much confidence — that all changed after the ride,” says Chavez. “I credit the ride for giving me the confidence to take on numerous challenges like joining the army, finishing college, and having a career in journalism. The ride changed me because it forced me to go past my limits – physically and mentally. So, afterward, I had the fortitude to not give up when things got tough or when it seemed like a task was impossible.”

For the last 27 years, Chavez has been an assistant editor for the Cherokee Phoenix, which was first published in Cherokee and English in 1828 in New Echota (present-day Georgia), then the capital of the Cherokee Nation (the paper’s offices are now headquartered in the new capital, Tahlequah, Oklahoma). In addition to his full-time position, Chavez has worked as the coordinator and trainer for the Remember the Removal Bike Ride for the last four years.

In addition to the inaugural ride in 1984, Chavez also participated as a mentor in the second iteration of the ride, 25 years later.

“In 2009, the chief at the time decided to bring the ride back and he consulted some of the original riders, asking how we did things,” says Chavez. “Except for 2020, it’s been going consistently since then.”

Today, the ride remains a youth leadership program for tribal members aged 16-24, with applications opening each year in September (there are also two mentor riders each year, for those 35 and older). The program interviews are comparable to a formal job interview — applicants are scored and selected by a panel at the end of October, before attending orientation in November.

"When I was chosen to be on the ride, I felt a sense of pride grow within me," says Whitney Roach, who completed the ride in 2021. "I not only get to represent myself and my family, but I get to represent my ancestors who were forced on the Removal…I [had] the opportunity to retrace their steps in remembrance of their strength and resilience."

Selected participants sign a contract, committing to six months of rigorous physical training, clocking miles but also learning how to clip in and use a bike with drop handlebars and lots of gears. There’s also a cultural training component that includes Cherokee lessons.

“Most of our youth don’t speak Cherokee these days so that’s part of the training,” says Chavez, adding that the cohort’s formal introductions to the tribal council are always in Cherokee. “They learn the language, the culture, and the history of the Trail of Tears. They end up with a really good background of what happened so that they’re prepared when they go out on the road and people start asking them questions.”

Along the ride, which starts in Georgia, riders visit significant sites, including New Echota, the former Cherokee capital; Kituwah Mound, the original Cherokee homeland; Blythe Ferry, where Cherokees gathered during their forced removal; Mantle Rock in Kentucky, where the former Trail of Tears route is a hiking trail; and many, many unmarked grave sites.

“There are so many points in history when the Cherokee people could have disappeared like some other tribes,” says Chavez, noting that in addition to surviving the Trail of Tears, the Cherokee survived a smallpox epidemic that decimated the tribe in the 1700s, the American Civil War in the 1800s, and the seizure of lands and destruction of tribal government the pushed the tribe into poverty in the 1900s. “Yet, we are still here today. From the standpoint of being a Cherokee person, the ride made me even more proud of who I am and even more proud of my ancestors for what they endured and survived,”

A body of research, published from 2020 to 2022, highlights the benefits of the Remember the Removal Bike Ride for participants’ physical, emotional, social, and cultural well-being. Past riders that were surveyed showed improvements in their diet and exercise habits, as well as their mental health, with reductions in things like stress, anxiety, depression, and anger. Perhaps most importantly, those surveyed also demonstrated improved social and cultural connection to one another, their Cherokee identity, and fundamental Cherokee values.

Participants from the 2019 Remember the Removal Bike Ride walk down a preserved section of trail used by Cherokees in Tennessee during their forced removal some 180 years ago.

Over the course of three weeks, the youth ride anywhere from 40 to 70 miles a day, some much more difficult than others (particularly those in Missouri, nicknamed “Misery” due to its constant heat, hills, and rough roads).

In 2021, the riders switched from using road bikes to gravel bikes, which makes traversing the mountains and backroads much easier. The Cherokee Education Department pays for rider’s helmets, shoes, sunglasses, a bike computer, custom cycling kits, and bikes, which are Fuji this year but have covered the gamut of quality brands over the last decade. To receive the kit, riders are required to pass a grueling 60-mile road test — friends and family are then invited to watch them receive their kits, an event with a strong ceremonial element. When participants complete the ride itself, they get to keep their bikes.

In an average year, Chavez takes 8-10 riders, although this year it’ll be a group of six, having lost two to injury. Interestingly, since 2018, the Remember the Removal riders have been trending female, and since 2021, the cohort has been completely female.

This years Remember the Removal cohort, which will begin their ride on June 5.

“Elders and council members have been asking, where are all the boys?” says Chavez, noting that male youth just aren’t applying. “Obviously, the girls aren’t afraid to do it — it’s tough and these girls want to take on the challenge.”

At the end of May, Chavez accompanied the riders to North Carolina, where they met up with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who also has a team of six riders. While the two tribes share a lineage, there are still a few differences in language, which can become apparent in the call signs used, all of which are in Cherokee. After a training ride together to get on the same page, the group will travel to Georgia, where they’ll begin the Remember the Removal Bike Ride on June 5, traveling nearly 1,000 miles through Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma.

Upon completion, the riders will join more than 200 alumni, many of whom are still as committed to the ride as Chavez is, showing up to help with training, mentorship, or on-route support. It makes sense — after all, Remember the Removal is first and foremost a spiritual journey. Not only does it test the endurance and emotions of those who participate, but it directly connects them to their ancestors. In riding, they remember where they came from and find the strength to go on.

If you’re interested in following the riders’ journey along the northern Trail of Tears route, tune in to the official Remember the Removal Bike Ride Facebook page.

Related Locations: