Six Secrets from the Man who Planned Sevilla’s Lightning Bike Network

By: Michael Andersen, PlacesForBikes staff writer

Here’s one way to understand the story of biking in Sevilla, Spain: It went from having about as much biking as Oklahoma City to having about as much biking as Portland, Oregon.

It did this over the course of four years.

Speaking last week at the PlacesForBikes conference, one of the masterminds of that transition — which is only now becoming widely known in the United States — filled in some of the gaps in that story.

Manuel Calvo had spent years in Sevilla bicycling activism and was working as a sustainability consultant when he landed the contract to plan a protected bike lane network for his city. The result was the Plan de la Bicicleta de Sevilla, mapping the fully connected protected bike lane network that would make Sevilla’s success possible.

But as Calvo explained in his keynote Wednesday and an interview afterward, the story might not have played out that way.

Here are some things for U.S. bike believers to learn from Calvo’s account.

1) Driving had been rising sharply in Sevilla for years before 2007

Spain’s economy was booming in the early 2000s. Andalucia, long a poorer part of the country, was enjoying that too. But the bad news was that suburbanization and car use were rocketing upward — trends Calvo and his fellow environmentalists knew needed to be somehow reversed.

“We were really worried about what was happening in Seville at that point,” Calvo recalled. “Only the poor people rode bicycles.”

On the bright side, Sevilla’s transportation department was flush with cash, thanks to fees collected from new housing construction. It had €32 million (about $42 million) to spend on something pretty big.

2) Politicians’ support for a major biking investment came from a single poll

As we wrote last year, a crucial moment for Sevilla’s future came in 2003. Seville’s local United Left party, led by the bike-supporting politician Paula Garvín, entered a political coalition with the local socialist party. Garvín became Sevilla’s vice mayor.

But the socialist mayor, Alfredo Sánchez Monteseirín, still needed to green-light the plan. The key to his decision, Calvo said, was a 2006 poll.

“We asked the people, ‘Do you think cycling infrastructure would be good for Seville?'” Calvo said. “And we got an astounding result: 90 percent.” (The phrasing and results are on p. 39 of this PDF.)

That was it, Calvo said. From there on, Monteseirín was sold. He decided that in the end, most of the city would be behind him.

Calvo said it’s a common story in many cities these days.

“When you ask the officials, the politicians, what they think about cycling promotion, they say, ‘Oh yeah, that would be a good thing.’ But when you ask them ‘What do the people think?’ they say, ‘Ooh, I don’t know.'”

“When you actually go to the people and ask them, the opinion is just the same as the politicians,” Calvo said.

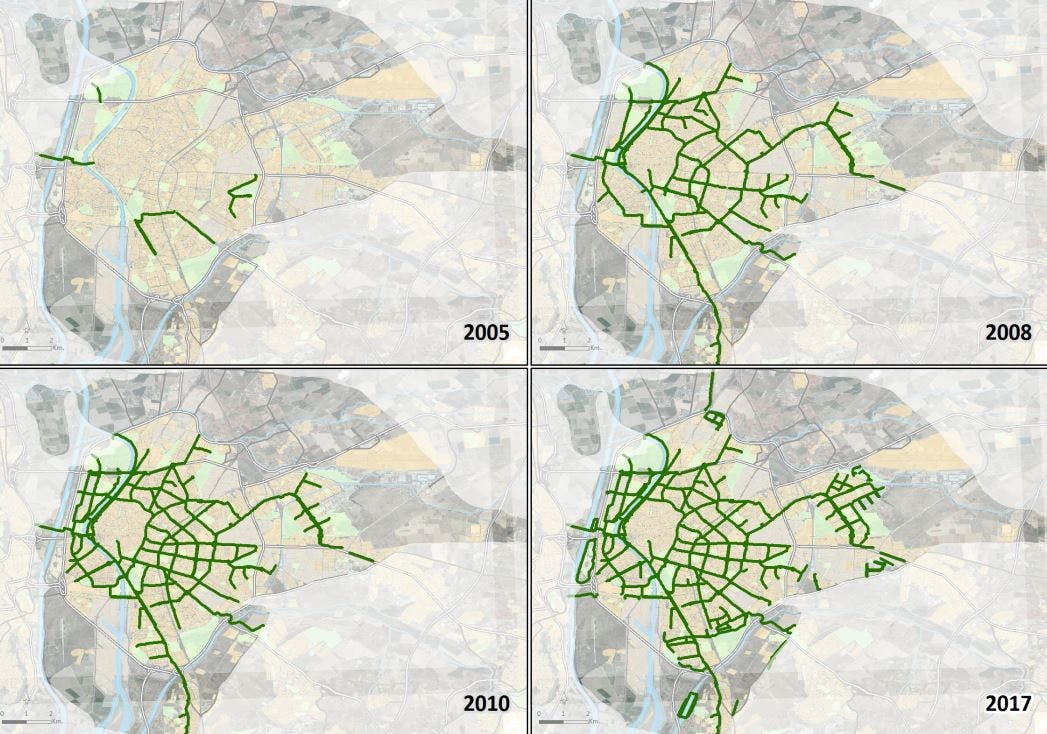

3) The network was built so fast because leaders saw a chance to deliver it within a single election cycle

The next question was how fast to build the network. Calvo said he approached José García Cebrián, head of the city’s urban improvement department, with a plan to build 10 kilometers of the network each year for eight years.

No, García told him. García said the entire 80-kilometer minimum grid needed to be built in 18 months.

“He had this vision of the network had to be in place really fast,” Calvo said. “He had the money, he had the will, he had the political commitment.”

One reason: unlike almost anything else a city can do, major biking improvements could be finished in time for politicians to brag about them in their next campaign.

“All of this had to be built before the elections — they had to sell something,” Calvo said.

Everyone knew it might backfire.

“It was a risky way,” Calvo said. But today, he said, delivering bike projects in the first two years of office is “what I advise to all the local governments.”

That’s about how long it takes a major biking project to pay off.

“You have to do everything in the first two years,” he said. “It starts working, and then people see that it works, and then people are supportive of what you did.”

4) Sevilla created its network by repurposing 5,000 on-street parking spaces

As it was installed, the plan was massively controversial. One prominent local journalist attacked the protected bike lane network as “useless,” saying that because so few Sevillanos biked at the time, Sevillanos never would.

But the city pushed onward.

“We got rid of nearly 5,000 parking spots for cars in the whole city,” Calvo said. “I can give you this figure now. For a while it was secret.”

“The media would ask us,” he recalled, smiling. “I’d say ‘Oh, we didn’t calculate that.'”

Even the design of Sevilla’s protected bike lanes was shaped by the looming risk of a backlash. Part of the reason the city built the network at sidewalk level was that it would make it vastly more expensive to unbuild if the Monteseirín-Garvín coalition lost power.

“That was José’s idea,” said Calvo. “He’s a lawyer. He’s always thinking ahead.”

5) Bike lane designs were shaped by public input – but only after officials made clear that doing nothing was not an option

For a project as lightning-fast as Sevilla’s, it’s easy to assume that the city simply ignored public feedback.

Not so, Calvo said.

“José was not afraid of talking to anyone, and was not afraid of modifying what you had to modify,” he said. “Especially in the university neighborhood, there was a big fight there. The project was totally modified there. Now it’s working perfectly. … The participation process was really important.”

The trick, Calvo said, is to set the expectation that public input will determine how to add bike lanes to a street, not whether to add them.

“In mobility issues, my experience is that consensus is impossible, because there are so many interests,” he said. “So you have to make an agreement with most of the people. But taking into account — being clear — that something is being done.”

6) Once the network was built, its benefits were obvious

The year after the basic network opened, Calvo said, it seemed like every family in the city had suddenly bought one another bicycles for Christmas.

“Everyone was talking about the success of the bike lanes at that point,” he said. “The sports shops, they ran out of bikes. They needed to get bikes from Barcelona, from Madrid, and over from France.”

Once that happened, it became clear that the huge bike network investment had been a fiscal bargain.

“The whole network is €32 million,” he says. That’s how many kilometers of highway — maybe five or six? It’s not expensive infrastructure. … We have a metro line that the cost was €800 million. It serves 44,000 trips every day. With bikes, we’re serving 70,000 trips every day.”

The governing coalition won their reelection in 2007 and continued improving the network. In 2011, after European Union austerity measures forced huge public spending cuts, voters returned a conservative coalition to office.

But by then, the onetime critics of bike lanes had changed their tune.

“Even the conservatives right now tend to be in favor of cycling,” Calvo said happily. “They’re complaining that the bike lanes are not being properly maintained.”

Related Topics: